Alex Honnold and his Fearless Brain

The brain activity of Alex Honnold, one of the best free climbers ever, was captured by neuroscience researchers. As such, the subject entered our radar as well. We hope it will interest you too.

There is also a verb derived from Alex Honnold's name: “Doing like Honnold”. Or to “honnold” in common parlance. It means standing in a high and risky place, with your back to the wall, looking into the bottomless pit you see below. That is to say, facing your fear.

The inspiration for this verb is the photographers shooting Honnold hundreds of feet above the ground in Yosemite National Park without any protection. Honnold walks off the side of the narrow cliff. It rubs against the wall as it goes. Toes touch the space. And yes, in 2008, he managed to become the first rock climber to climb the full granite surface of Half Dome alone and without any ropes.

Had he lost his balance for a moment, it would have taken 10 seconds to fall to the ground visible far below. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. Ten. It makes you sweat even when you think about it! So, what's going on in his brain when Honnold is doing all this?

Is Fear Manageable?

Honnold is the greatest free solo climber the world has ever seen. He climbs without using a rope or any protective equipment. That means he's face-to-face with death for hours during those epic moments of solo climbing. In fact, sometimes their fingers don't touch the rock any more than most people touch their phone screens. Just watching one of Honnold's videos leaves many people dizzy. Or it can cause heart palpitations and nausea. Sure, if they can watch the videos. Even Honnold had sweaty palms watching himself.

All this makes Honnold the most famous rock climber in the world. He has appeared on the cover of National Geographic, in 60 Minutes, in commercials for Citibank and BMW, and in many viral videos. In his interviews, he insisted that he felt fear. But with his actions, he has also become one of the symbols of fearlessness.

So, what's going on in Honnold's brain while he's doing all this?

In the photo below, MRI technician James Purl and neuroscientist Jane E. Joseph lead Honnold into an MRI tunnel to measure the level of fear in his brain. ©2016 NGC Network International, LLC and NGC Network US, LLC

Within neuroscience research, Honnold looked at nearly 200 images zapped between channels. They wanted the photos to disturb or excite Honnold. And so they did the viewing. These types of tests are very useful for neuromarketing research. The photos they use are the kind that normally evoke a strong reaction in most people's amygdalas. Even the researcher says; “Honestly, I can't even stand to look at some of them.” Among these images, there are displaced corpses, some parts of the face covered with blood. Or a toilet full of feces. There's also a woman shaving her hair Brazilian style and two stimulating mountain climbing scenes.

“Perhaps Honnold's amygdala is not regenerating; there is no internal response to these stimuli,” says the researcher. “But maybe there is such a honed regulation system that when he sees stimuli like this he says, 'Okay, I'm feeling all this, my amygdala is on fire. But his frontal cortex is so powerful that it can calm him down,” he adds.

Scan Results

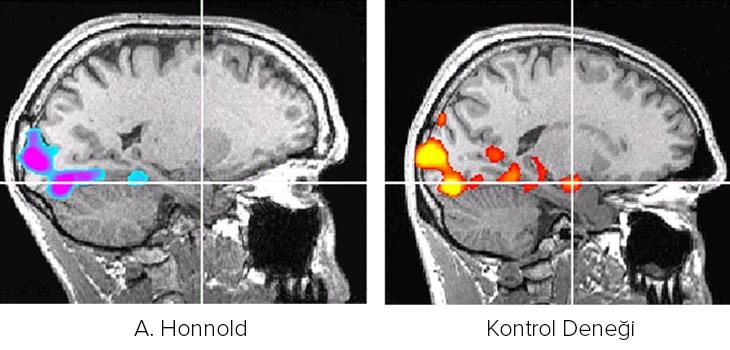

The scans compare Honnold's brain (left) to that of a rock climber of similar age—a control object (right). The center of interest points to the amygdala. There also seems to be a group of fear-inducing cores at work. Both climbers are looking at the same warning images. But while the control object's amygdala is on fire, Honnold's shows no activity. You can look at the area with the + sign in the photo. The areas marked with + in the photo show the amygdala. The control object's amygdala is active. But Honnold's has no activation at all. ©2016 NGC Network International, LLC and NGC Network US, LLC

To compare Honnold's amygdala in the study, they did this. They used another rock climber of similar age in pursuit of high excitement as a control object. Just like Honnold, the control object said that what he saw in the scanner did not warn him in any way. But in fMRI images of the two men's responses to these highly stimulating photos—where brain activity is marked with electric purple—the control subject's amygdala is highly active. Whereas Honnold's amygdala is grey. So it doesn't work in any way.

The researcher says the control object's amygdala and other brain structures "look like a luminous Christmas tree." The only activity in Honnold's brain is in areas that process visual input which is data confirming that he's just awake and looking at the screen. Yet there is no sign of life in the rest of the brain. As a matter of fact, it's just black and white.

“Not much is going on in my brain,” Honnold says absently. “It doesn't do anything.”

So why do people do such things?

The "brain reward center" near the brain stem is one of the main processors of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that induces desire and pleasure. People who are chasing high emotions and desires need more stimulation than other people for the necessary dopamine. We are highly adaptable beings.

Adaptation to these conditions is what lies behind Honnold's no-rope climbing to places where almost anyone would lose himself. According to the researchers, Honnold's brain was not activated and probably did not react to the threat. Anyone climbing at those heights must already have an extraordinary brain. As a result, neuroscientists were unable to detect any activity anywhere in the fear center in Honnold's brain.

A neuroscientist named Joseph LeDoux (New York University), who has studied the brain's response to threat since the 1980s, says he has never heard of anyone with a normal amygdala that shows no signs of activation but like Honnold's. He even considered the possibility that Honnold might have burned his amygdala from overstimulation.

There were times when Honnold thought about how he had overcome fear. Of course, he said to himself, "This is not a terrible situation.“Because that is exactly what I do.”

To read the original article: ”Nautil.us: Strange Brain of The World's Greatest Solo Climber”.